User:Thomas Wright Sulcer/Dactylic hexameter: Difference between revisions

imported>Thomas Wright Sulcer m (→Background: wikilink fix) |

imported>Thomas Wright Sulcer m (→Structural points in dactylic hexameter: wikilinx) |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

===Structural points in dactylic hexameter=== | ===Structural points in dactylic hexameter=== | ||

The dactyl serves as the basic rhythmic unit, or [[metron]], of [[hexameter]] [[verse]]. The word hexameter also derives from Greek and essentially means "six metrons (or ''metra'') in a row." In other words, a single epic verse consists of six successive dactyls, as the diagram shows. | The dactyl serves as the basic rhythmic unit, or [[meter (poetry)|metron]], of [[hexameter]] [[poetry|verse]]. The word hexameter also derives from Greek and essentially means "six metrons (or ''metra'') in a row." In other words, a single epic verse consists of six successive dactyls, as the diagram shows. | ||

[[Image:Idealized hexameter verse.jpg|thumb|right|300px|alt=Diagram.|The idealized dactylic hexameter consists of six dactyls or "feet" in a row such as this one.]] | [[Image:Idealized hexameter verse.jpg|thumb|right|300px|alt=Diagram.|The idealized dactylic hexameter consists of six dactyls or "feet" in a row such as this one.]] | ||

Revision as of 06:37, 21 April 2010

This is a draft in User space, not yet ready to go to Citizendium's main space, and not meant to be cited. The {{subpages}} template is designed to be used within article clusters and their related pages.

It will not function on User pages.

Dactylic hexameter is a form of meter in poetry used primarily in epic poems such as the Iliad and Odyssey by the Greek bard Homer and the Aeneid by the Roman poet Virgil. It is a fairly complex rhyme scheme. It is also known as "heroic hexameter". It is traditionally associated with classical epic poetry in both Greek and Latin and was considered to be the Grand Style of classical poetry. It is used in Homer's Iliad and Odyssey and Virgil's Aeneid. As a rhyme scheme, it works well with Latin and Greek languages, but there have been not many works in which English poems have been set successfully using dactylic hexameter. In English, it sounds like an "oomph-pah oomph-pah" sound if followed closely, and poets have been reluctant to use it; but in the original Greek language, dactylic hexameter flows smoothly and beautifully, according to classics scholar Elizabeth Vandiver.

Most likely the dactylic hexameter began during the oral tradition of Homer. There is speculation among scholars that the oral tradition was popular in the centuries of the early Classic period. Most likely the first versions of the Iliad and the Odyssey were written down sometime in the seventh century BCE, although scholars debate exactly when and how this happened. It is generally established that the Iliad and Odyssey were based on a tradition of oral presentations by bards, who recited the long poems from memory, but there is considerable debate about whether Homer was one poet or a combination, or whether Homer wrote down verses from memory, or how exactly the poems were transcribed. The Greek alphabet began around the eighth century BCE or earlier, according to evidence of the earliest surviving literary works.

Generally, Homer established some fairly firm rules regarding the epic poem, although there were later variations. Epic poems were probably accompanied by music with changes in pitch to highlight the melody, although there is no consensus view on how this worked.[1]

The Romans adapted the hexameter for their own purposes, but since singing the verses was no longer done, poets generally observed the "rules" of dactylic hexameter without reference to the sound. The Latin language has a greater share of longer syllables than Greek which lent itself to substitutions in which dactyls were replaced by spondees. As a result, Latin hexameter was described as more spondaic than Greek hexameter. Latin poets using hexameter included Ennius, Lucretius, Catullus and Cicero. They established firm principles which were followed by later Roman writers such as Virgil, Ovid, Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, and Juvenal.

Writing dactylic hexameter

Background

Greek and Latin poems follow certain rhythmic schemes, or meters, which are sometimes highly defined and very strict, sometimes less so. Epic poetry from Homer on was recited in a particular meter called the dactylic hexameter. Epic poems are composed in hexameters and hexameter rhythms suggest strongly that the poem being recited is an epic. There is substantial speculation that in the time of Homer, epic poems were accompanied by music such as on an instrument called the lyre, but in the time of Virgil, epic poetry was spoken without accompaniment.

The word dactylos is Greek for "finger". It also means "toe", which is allied with the idea of meters being thought of in terms of feet. The dactyl is a rhythm-bit that resembles, at least aurally, a finger and consists of one long syllable (noted as a straight line), which represents the long bone, or phalanx, of the finger, plus two short syllables (diagrammed like the letter "u"), which represent the two short phalanges.

The meter consists of lines made from six or "hexa" feet. In strict dactylic hexameter, each foot would be dactyl, but classical meter allows for the substitution of a spondee in place of a dactyl in most positions. Specifically, the first four feet can either be dactyls or spondees more or less freely. The fifth foot is almost always a dactyl -- around 95% of the time in Homer. The sixth foot is always a spondee, though it may be an anceps. Thus the dactylic line most normally looks as follows:

- — U | — U | — U | — U | — u u | — —

(note that — is a long syllable, u a short syllable and U either one long or two shorts)

As in all classical verse forms, the phenomenon of brevis in longo is observed, so the last syllable can actually be short or long.

Rhythmically the two short syllables are equivalent in tempo to the long syllable; in the same way, in music, two half notes equal one whole note. Think of a dactyl as sounding like the words "dum-diddy," with "dum" equal to a long syllable sound, and "diddy" equal to two short syllable sounds.

An English language example:

- Down in a | deep dark | hole sat an | old pig | munching a | bean stalk

It follows this general form:

- dum diddy | dum dum | dum diddy | dum dum | dum diddy | dum dum

Quantitative meter is difficult to construct in English, but easier to do in Latin or Greek. Here is an example in normal stress meter. It's the first line of Longfellow's "Evangeline":

- This is the | forest pri | meval. The | murmuring | pines and the | hemlocks

- dum diddy | dum diddy | dum diddy | dum diddy | dum diddy | dum dum

The "foot" in a poem is often compared to a musical measure. The long syllables are like half notes; the short syllables are like quarter notes.

Homer arranged words to emphasize the interplay between the metrical ictus—the first long syllable of each foot—and the natural spoken accent of words. If ictus and accent coincide regularly, what happens is that they over-emphasize each other and the hexameter suffers from a "sing-song" effect. Still, some reinforcement is desirable to keep up the poem's natural rhythm. The best poems balance both considerations -- so the verses have a nice rhythmic beat but they're not too predictable, and there is tension between how the words are meant to be said (by the poet) and how the words are actually spoken. These considerations led to a series of rules to put pauses (called caesura) in the line, and to break up any monotony.

Later poets like Virgil followed the rules closely but looked for ways to exploit the effects. One line in the Aeneid (VIII.596) describes the movement of rushing horses and how "a hoof shakes the crumbling field with a galloping sound": quadripedante putrem sonitu quatit ungula campum. The line has five dactyls and a closing spondee which is an unusual rhythmic arrangement, but it was done because it imitates the sound of the horses galloping. In another line, Virgil chooses spondees primarily to make the sound of a blacksmith pounding out a shield. He describes how the blacksmith sons of Vulcan "take up their arms with great strength one to another" in forging Aeneas' shield: illi inter sese multa ui bracchia tollunt. This line has all spondees except for the usual dactyl in the fifth foot. The effect mimics the pounding sound of the work described in the poem. Virgil uses dactyls and spondees creatively to emphasize other sounds, such as lightning bolts hurled by Jupiter. Virgil broke the strict metrical rules to create special effects; for example, to describe a ship at sea during a storm, Virgil violated the metrical rules and placed a single-syllable word at the end of the line: et undis then dat latus; insequitur cumulo praeruptus aquae mons. By placing the monosyllable mons at the end, Virgil interrupts the usual "shave and a haircut" pattern to achieve a jarring effect that echoes the crash of a large wave against a ship.

Structural points in dactylic hexameter

The dactyl serves as the basic rhythmic unit, or metron, of hexameter verse. The word hexameter also derives from Greek and essentially means "six metrons (or metra) in a row." In other words, a single epic verse consists of six successive dactyls, as the diagram shows.

The final metron is technically not a dactyl; its second syllable is called the anceps which is Latin for "two-headed". No hexameter verse ends in two short syllables; rather, hexameter verse ends in the anceps (either short or long -- it doesn't matter). In fact, when reciting, the anceps is always treated as if it was long to fill out the line.

A more common word for metron is foot. The origin of this idea is that a "line of metra" marches past the ear during a recitation. So marching sounds have been put into poetry. The long syllable which is the "first half" of the foot, is like putting one's foot down, and the Greek language term is thesis meaning "putting down", because the foot is imagined as touching the ground. The two short syllables are the logical opposite in which the foot is "lifted up" or "raised up", and is called in Greek the arsis meaning "lifting up". This prepares the foot for the next "footstep".

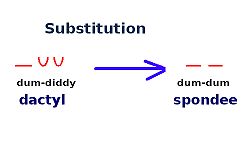

The general strategy when writing a poem in hexameter verse is to insert words into the metrical scheme where they fit. But a continuing problem is that not every word has a short syllable or even two short syllables. So how is this problem solved? Ancient poets devised various conventions to bend the rules to allow for the wide variety of syllables in words. Poets can substitute a pair of short syllables for a long syllable. So, at his or her discretion, a poet can switch in a pair of short syllables for a long syllable, in an allowable principle called contraction, so that a particular dactyl becomes a spondee. So every foot in a hexameter verse has the potential to be either a dactyl or a spondee, although there are customs that the fifth foot usually remains a dactyl. And the last foot usually stays as an anceps. But every foot in a hexameter verse has the potential to be either a dactyl or a spondee.

The next step in writing hexameter verse is called scansion or scanning (from the Latin word scandere which means "to move upwards by steps"). It's a process or art of dividing a verse into metrical components. It's different from reciting verse when the aim is to preserve both the sound of the poem as well as the rhythm and beat of the words; rather, at this stage, the process of scansion seeks to determine whether syllables are long or short, and to group them into feet. A syllable is a "unit of uninterrupted sound in a spoken language". Sometimes it helps a person, who is planning to recite verse, to scan it first because it's excellent preparation. A skilled person can recite and scan hexameter verses simultaneously.

But is a syllable long or short? Here are three rules-of-thumb for determining whether syllables are long or short:

- A short syllable contains a short quantity vowel, such as the nominative singular ending of the first declension.

- A long syllable contains a long quantity vowel, such as the ablative singular of the first declension.

- A long syllable may also contain a diphthong (two vowels pronounced together), such as the genitive singular of the first declension: . The -au- in nauta is also considered long under this rule.

- A syllable is considered long when directly followed by two consonants, whether in the same word or beginning the subsequent word. For instance, if the nominative version of "nauta" immediately precedes the verb "scit", the final -a becomes long by position: "nauta scit" (with "nauta" have a long syllable sound). This rule is not ironclad, as certain consonant combinations—like -cr, -pr, and -tr—will not "make position."

Breaking a verse into feet often means breaking up syllables. For example, suppose one wanted to take the following line and break it up into what is called syllabification: arma virumque cano. How is this broken up? It's broken up like this: arma vi | rumque ca | no. But it shouldn't be broken up like this: arma vir | umque can | o. What determines the proper way to do syllabification, that is, the process of dividing words up into the respective syllables, is a series of rules:

- Syllables are usually divided between a vowel and a single consonant, particularly when the vowel comes first: vi-rum, not vir-um.

- When a vowel is followed by two consonants in the same word, breaj between the consonants: ar-ma, not arm-a or a-rma.

- An exception to this rule happens if a vowel is followed by a stop (a consonant formed by complete air blockage, for example t, d, p, b, k, g) plus a liquid (a consonant that can be prolonged, for example, l or r). So patres divides as pa-tres, not pat-res. A stop-liquid combination, as a matter of fact, will not "make position" for a vowel: the -a- in patres scans as short, not long.

The contraction of dactyls into spondees enables flexibility since it allows more chances for word placement within a verse. Sometimes syllables were ignored altogether through a process called elision (Latin for "knocking out"), which ensured further flexibility. The first rule of elision is:

- A final syllable ending in a vowel may be omitted from the meter before a word beginning with a vowel (or an h-). For example, the phrase "nauta est" is technically three syllables long; but because est begins with a vowel and nauta ends with one, the final -a is elided, that is, it's "knocked out" and ignored, for a total of two syllables: nauta est is pronounced something like now test. It's the same principle in English when a vowel is dropped when the words do and not contract to form don't. According to the rule, the syllable may or may not be omitted; it's up to the poet and reader what happens. But when a syllable could be dropped during elision but it is kept in, the technical term for this deliberate avoidance of elision is called hiatus which is Latin for gap.

The second rule of elision is:

- A final syllable ending in the letter -m may be omitted from the meter before a word beginning with a vowel (or an h-). So nautam est is elided to naut-est (again pronounced: "now test").

Within every verse comes at least one opportunity for a pause, a brief halting during the reading of the line. This pause, called a caesura which is Latin meaning "cut", often accompanies a pause in the meaning of the words. The purpose is to let an idea "sink in" before another is introduced, like a breather or brief intermission which helps the mind fully absorb a thought. As a result, caesurae always occur between words, one at the end and one at the beginning of a clause. In addition, a caesura always appears in the middle of a foot not at the beginning or end of a foot. And the caesura can happen:

- within the arsis itself, between the two shorts.

In the following drawing, the double blue lines indicate the caesura. Caesurae inside an arsis are considered weak, while those following a thesis are strong. In theory a caesura may occur in any of the six feet. Most verses have two or more caesurae. The principal caesura marks the most obvious pause in the sense of the words and usually happens in the third foot, although it can happen in the second or fourth foot as well. But there are many possibilities. [[Image:Principal caesura.jpg|thumb|right|300px|alt=Diagram.|There are five caesurae in this line but the main one is in the third foot and places a pause between the main clause arma virumque cano and the relative clause qui primus ab oris Troiae.

A primary caesura is similar to a comma in prose. There are several normal positions for a primary caesura:

- After the first syllable in the third foot; this is called the "masculine" caesura.

- After the second syllable in the third foot (if the third foot is a dactyl); this is called the "feminine" caesura

- After the first syllable of the fourth foot OR after the first syllable of the second foot. The latter two often occur together in a line, breaking it into three separate units. Generally, the first possible caesura that one encounters in a line is considered to be the main caesura.

When dividing a verse into feet, divisions are often made within the words themselves. What happens is that the boundaries between feet rarely correspond to the boundaries between words. But when the end of a foot coincides with the end of a word, the resulting division is called a diaeresis. Diaeresis means "division" in Greek. A diaeresis differs from a caesura in that it must occur between feet and it does not necessarily mark any discernible pause in the meaning. Here's a diagram:

What is the big deal about the diaeresis? It's because the line is seen as a distinct metrical unit with a life of its own. The words primus ab oris ends the verse with a recognizable "dum-diddy dum-dum". It sounds in American English like shave and a haircut or in the U.K. as strawberry jam-pot. It's a rhythmic snippet. Since the word primus begins a new foot, it's easy to recognize. When a diaeresis happens between the fourth and the fifth feet, it is called a bucolic diaeresis after the Greek boukolos meaning "herdsman". Apparently herdsmen poets used the dum-diddy dum dum or shave and a haircut endings often.

While the rules of dactylic hexameter can be strict and complex, in practice the verse allows a reader to change the tempo and rhythm to create a dramatic effect. There are places within each line where a strict metrical arrangement won't be effective, particularly at the beginning of a line when the thesis conflicts with a word's natural accent.

Further information

- Sources: Skidmore's Classics 202 Intermediate Latin II. Glossary of terms relating to dactylic hexameter

References

- ↑ Cf. Alan Shaw's essay Some Questions on Greek Poetry and Music.